- Home

- Shannon Giglio

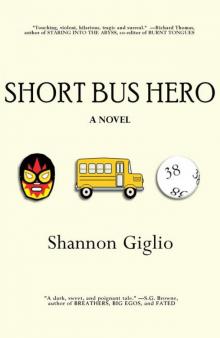

Short Bus Hero

Short Bus Hero Read online

SHORT BUS HERO

Shannon Giglio

Short Bus Hero

Copyright © 2014 by Shannon Giglio

This edition of Short Bus Hero

Copyright © 2014 by Nightscape Press, LLP

Edited by Robert S. Wilson

All rights reserved.

First Electronic Edition

Nightscape Press, LLP

http://www.nightscapepress.com

for Megan and Linda

1. Chronophobia / kron´-o-fo´-be-ә / fear of time

It could be the blinding stream of headlights. It could be the freezing rain. It could be Mara, singing loud and off-key in the passenger’s seat. But, come on—let’s cut the crap. It’s the heart attack. Well, that and people driving like complete morons—but, no, it’s the heart attack. That’s what starts it all, this whole freaking mess. Ally’s journey to fame, Stryker’s complete one-eighty, the restoration of my faith in the human race—it all starts with a massive heart attack.

A gray veil unfurls in front of Sylvia’s eyes as she waits for the light to change. Her head buzzes and her ears and cheek flush hot. Blood backs up and double parks in constricted vessels meant for through-traffic only. She unzips her jacket. Route 51 is congested, even for a Friday. She glances over at Mara, wondering if she should pull over for a minute and try to catch her breath or get out and walk around or something. A horn honks behind her. The idiot in the SUV with his high beams on, on a busy four-lane highway, must be in a hurry. Jerk.

How long has the light been green?

“Mom, go!” Mara yells from the passenger seat, extra loud because of the headphones jammed into her ears. She doesn’t want to be late for the Cool People’s weekly karaoke night at the Jefferson Hills Recreational Center. She lives for shouting out the wrong lyrics to today’s most popular hits, clapping in all the wrong places, spitting cheese bread on the foam-covered microphone. She can’t wait for Jason to see her new haircut. Maybe he’ll ask her out instead of Ally.

Earlier that day, Sylvia had been feeling queasy and begged off her book club. She hadn’t thought much of the icepick stabbing her beneath her sagging jaw line. It hadn’t been killing her or anything. She’d thought about maybe scheduling an appointment with the dentist. Or maybe Mara’s chiropractor—he’d done wonders for her daughter’s neck pain and laxity. Anyway, by the time Oprah came on, Sylvia had felt better and saw no reason for Mara to miss out on the high point of her week. So, they’d headed out to the rec center. Sylvia had been looking forward to having dinner with the other mothers, too. Jason’s mother, Trish, was bringing pictures of her recent trip to see her grandchildren, and that was always such a treat. Kept ol’ Syl sane, anyway.

As she fights to focus on keeping up with the glut of traffic, an invisible hand squeezes her shoulder harder than a pipe-jawed industrial vise. Route 51 isn’t the only thing clogged. Platelets pile up in her left coronary artery, filling a breach in the plaque that lines her circumflex artery. She struggles for a breath but an unseen elephant has somehow managed to wedge itself in between the steering wheel and her sternum. The left atrium of her heart starves for oxygen as blood is diverted to collateral vessels. Her circulatory system backs up. She feels like somebody is pulling a hood over her eyes. Her adrenal gland kicks into overdrive and she feels like throwing her door open and running away. Her mouth works like a fish out of water. Her right hand leaves the steering wheel and flails in Mara’s direction.

The pickup truck she’d been tailgating swerves into the left lane and Mara screams as their Dodge Caravan plows directly into the rear end of a stationary Pittsburgh city bus.

The entire wreck unfolds in slow-motion: the inward crush of the Caravan’s rounded nose, the popping and crunching and squealing, the glittering spider web of fractured safety glass, the Midnight Blue Pearl bruise on the white bumper of the bus as the van rebounds, the hot ammonia stink of the wetness spreading into the seat beneath Mara as she screams into her hands.

Sylvia can’t see anything but the rough canvas that balloons into her face with the force of a heavyweight’s punch, cracking her nose and fanning a spray of crimson across the driver’s side window. Her left foot stomps off the brake pedal’s rubber covering. The exposed corner of the lever’s steel skeleton bites into her right calf, splitting it deep up the side, exposing muscle and bone. A plane of carpeted metal beneath the steering column collapses inward, folding Sylvia’s left toes up to her tibia. Lateral and medial malleolus bones snap, their ragged edges stabbing through the parchment of her skin.

The world crashes to a fractured standstill, leaving an ugly black skid mark on the evening.

It is a total clusterfuck. Cars up and down Route 51 slam to a stop. After a moment of shocked silence, people crowd around the van, shouting at each other and into their cell phones, struggling to open the Dodge’s crumpled doors. Others lay on their horns, in a rush to get to whatever life-or-death function they’re trying to get to—you know, like the seven o’clock showing of Saw X or the fifty percent off sale at JC Penney.

Sylvia doesn’t notice any of it.

The hood draws over her eyes and all she can think is that Mara is going to miss karaoke night.

* * *

Antiseptic, fear, excrement, vomit, desperation, death. No matter how many times I walk the supposedly sterile corridors, I’ll never get used to the singular human stench that haunts the place. It makes me sick, decade after decade. Call it a job hazard. Accompanying the olfactory assault is a no less disturbing auditory attack: hushed conversations punctuated by acronyms, cries for help, retching, sobbing, the hollow clicking of plastic tubing against metal frameworks, disembodied robotic beeps, the clackity-squeal from the wheels of a passing gurney, distraught families gaping at haughty doctors basking in their own little God complexes.

Could be Hell on Earth, you know?

I mean, I’ve never seen Hell, but I’m just saying.

The UPMC Emergency Room is definitely a complicated place. Lives can be saved with one single shot of some synthetic chemical or just the right electric jolt. But, Death always crouches in unlit corners, held at bay by the tenuous combination of knowledge and luck. So many times the synergy fails and The Boss stakes his claim.

And what do I do about it?

What can I do, really?

I stand aside and watch my Superiors perform their duties. They say there’s no other way. They say they do it for The Greater Good. They say no human lives forever. I used to ask why, why, why, until I realized I’d never get a straight answer.

It’s disgusting and I am so over the whole thing.

I make my way down the hall, dodging nurses in surgical caps and cartoon patterned scrubs, peeking through drooping and stained damask privacy curtains, unseen in the Friday night chaos. I search until I find her. The body, lying supine and still on the gurney, belongs to one pale and fragile sixty-two year-old woman: Sylvia Heffron. Bus Wreck Babe of Pittsburgh.

Young doctors in long white coats, barely ambulatory themselves after being on call for so many endless hours, stand around the stretcher. They call out for medications and tests—necessary and unnecessary—as nurses and orderlies scurry around behind the pulled curtains, passing in and out of the collapsible room, carrying trays of sterile and frightening tools and instruments.

Man, I hope this woman has health insurance. (I’m sure the hospital has already verified her coverage.)

Sylvia’s best friend, Lois Forman, and I arrive outside the damask wall at the same time. Lois is intercepted by a stern-looking nurse as I slip through the curtain, unseen. As I pass, I hear Lois ask what happened, to which the nurse begins her hushed and rote reply: “I’m so sorry…”

I feel so damned tired.

>

These stupid humans and their bloody fragility.

The worst part of it is, you will never learn.

Anyway, I feel bad for Lois.

By the way, this is Lois’s daughter’s story, but we have to start here, in this freaking hideous place, with unlucky Sylvia. She sets this whole thing in motion. Call her our catalyst.

The widowed Sylvia. Active in the Order of the Eastern Star (her dear departed husband had been a Freemason); member of St. Martin’s-in-the-Field Reformed Episcopal Church; voracious reader and book club member (mysteries are her favorite); mediocre but enthusiastic bowler; and, of course, selfless, tireless mother, champion, and constant companion to lovely Dear One, Mara Heffron.

And it is the last item on the list which has brought me to her bedside in the UPMC Emergency Room.

Mara is Ally’s best girl friend.

* * *

Lois and I hang out in the waiting room as her friend teeters between worlds. I watch transfixed, as new lines of care are drawn at the edges of her eyes and around her mouth, by a gentle instrument that would scare the crap out of her, if only she could see it. It hurts way more than getting a tattoo, doesn’t it, all those wrinkles accumulating on your face? Worrying for years on end for every one of those little buggers. At least a decent tattoo can be finished in a matter of an hour or so.

She murmurs to her husband on her cell phone when she thinks the room is empty. He picked up Mara from the ER hours ago. The doctors released her after checking out the scrapes on her face and hands that she got from her airbag. Earl took her home to spend the night with their daughter, Ally.

Yes, the Ally.

He’s a good guy, Earl Forman. Lois hangs up the phone, grateful that he’s hers. Grateful that he’s not some unemployed drunk who doesn’t give a monkey’s earlobe about his family. She knows quite a few of those in their own neighborhood. She stands up from the floral-patterned sofa she’s been planted on for hours, and stretches. Not in the mood for David Letterman, she crosses the room and switches off the television that hangs in the corner. Lois looks around at the brown and peach-colored furniture, the yellow pools of light that ooze from garage sale table lamps onto scarred oak end tables, the gritty gray linoleum floor, a frayed wicker basket full of outdated and rumpled magazines. She suppresses an urge to grab the basket and take it home, to squirrel away the magazines in her basement. She slams some internal door on the thought.

Lois silently asks God to help her friend, then she walks to the window, perhaps to look for Him in the twinkling lights of the city below. Her eyes track left to right in her search.

Yeah, good luck with that.

Sometime later, a guy in green scrubs opens the door and pokes his pointy head into the room. Lois turns, perking up, ready for news. The man just smiles at her and leaves. Must be looking for someone else.

Lois tries to lie down on the short sofa, but it’s too uncomfortable. She gets an instant cramp in her neck from trying to squeeze on. She pulls a chair closer to the couch and puts her feet up. Didn’t she know the Sandman doesn’t visit the hospital unless chemically invited?

There is nothing I can do to comfort her. I don’t know anything about Sylvia’s condition. Lois will just have to wait.

All I can say is: sucks to be human.

She turns the television back on, tries to follow some brainless old sit-com. Archie Bunker. That guy cracked me up. Idiot from an even more uneducated era.

Finally, a doctor and a nurse enter the room. The doctor sweeps the SpongeBob surgical cap from his bald head and looks Lois in the eye.

“Ms. Heffron is out of surgery.”

* * *

“What am I going to do?” Sylvia croaks. from the bed in the semi-private room they’d wheeled her into after her emergency surgery. Lois stands at the window, watching the morning shadows play behind Heinz Field, the new casino, and the Science Center. She’s been at the hospital for many sleepless hours and wishes for some duct tape to hold her eyelids open. She jumps at the breathless voice. She didn’t know Sylvia was awake.

Even with her senses dulled by the liquid calm that flows through her veins, Sylvia notices that Lois looks older than her sixty-odd years, and anxious behind a translucent mask of bravery.

“I can’t stand the thought of putting her in some home, with strangers,” Sylvia huffs, her puffy eyes welling up. She tries to stifle a cough. Or a sob. Lois thinks—rightly so—that she probably shouldn’t be speaking yet, but she understands the desperation that drives her to risk it. Lois has been thinking about the tragedy of the situation for hours. Old single mom, disabled child with no family...

Lois turns from the window and collapses into the chair beside her friend’s bed. She gazes at the empty bed near the door, trying to summon some coherent thought through the buzz of shock that vibrates somewhere behind her eyeballs. A cold draft seeps through the room.

That’s me.

The tiny hairs on her arms stand up and she feels, just for a second, that they are not alone. Even though I know she can’t see me, I instinctively step into the shadows behind the bunched curtain that bisects the room. She clears her throat, trying to shake the feeling of being watched, and reaches over to brush the shock of white hair from Sylvia’s forehead.

“Honey, you can’t worry about that right now. You made it this time—be thankful. But, when our time comes, it comes, whether we’re ready or not.” Lois wipes her eyes with a crumpled tissue from her coat pocket. She stuffs the Kleenex in her pocket. She’ll add it to her collection in the shirt box underneath her bed when she gets home. “Ally’s going to live with her brother after Earl and I are gone. Can you imagine how I feel about that?” She snorts. “And, I know that Jason’s going to his brother in New Jersey.”

What? That was supposed to offer some kind of comfort?

Sylvia didn’t know, didn’t know where Ally and Jason were going “when the time came,” and she didn’t find it very consoling. She didn’t know anything at that moment. She is scared and confused and more worried than she’s ever been. Lois’s comments fill the room like some kind of toxic fallout. Lois herself wishes she hadn’t said it.

Yeah, “open-mouth-insert-foot.” That’s Lois.

Sylvia starts crying. Her strangled sobs cause her machine that goes ping to ping erratically.

“Mara doesn’t have anyone.” Lois offers Sylvia a tissue. Sylvia wipes at her broken nose, trying to clear the drippings that work their way out past the plastic tubes occupying her nostrils. “But,” she sighs, “that’s not really why I’m crying.” She forces a pathetic laugh. “I mean, yes, it is, but I’m also crying because these kids.” She manages to smile, a quick upturn of the corner of her swollen lips, like a tic. “I know they’re in their twenties now, but you know they’ll always be ‘kids’ to me. They’ve been together since they were babies.”

“I know,” Lois says, smiling through their communal pain. “I remember the day we met you and Mara, up at the school.” Ally and Mara were four years old then, tearful and terrified by the prospect of being left with the kind-but-unfamiliar teacher. Lois and Sylvia sat side by side in miniature chairs, their knees poking up higher than the children’s table in front of them, anxiously watching their daughters swing dolls by the hair and throw blocks on the floor. At the end of the assessment, the two women had exchanged phone numbers, planning to meet for coffee the following week. Each had felt as though they’d finally met someone who they didn’t have to pretend with, like they did with other “normal” moms. That day, unbeknownst to them, the Cool People group was born. “It’s so hard to believe that was twenty years ago.”

Sylvia takes a long ragged breath. “It’s even harder to believe there may not be twenty more,” she says, sobbing. After the crash she’d had a quadruple bypass and surgery on the compound fracture of her left ankle. Mortality was shoved to the very forefront of her mind.

Lois cries, too, and holds her friend in a familiar embrace. She can’t remem

ber when Sylvia had gotten so thin. She can feel her skeleton and the sensation unnerves her. When had they gotten so old? It was strange, their aging while their children remained perpetually twelve years old. Unfair, Lois thought. Unfair, even I thought.

Stupid human condition.

You humans just don’t know how to take care of yourselves.

Anyway, it was Lois that I’d been assigned to that night, not Sylvia. Lois, who had always been the de facto leader among the Cool People’s parents. Lois, mother of my Dearest One, Ally. I had to see how she’d present all of this to her beloved mentally challenged daughter and what she could do to protect that Dear One from a future world without parents.

I step forward and bend my head to Lois’s. I speak at some length in quiet but firm tones, words meant only for her. I mean, not that Sylvia could hear me—even if I screamed—but, you know, I don’t want to scare Lois or anything. I’ve never spoken to her before.

She thinks she’s hearing things.

Then, she decides she’s having an idea.

“Syl,” she pushes her friend away, holding her at arm’s length, “What if we could keep them together?” Lois laughs at the simplicity of the idea. They all do that. Everyone I counsel, I mean. They all mimic that exact same reaction after I whisper in their ears.

It used to make me smile.

Ah, I used to so enjoy dispelling the innumerable palpable and crushing burdens from fragile flesh-covered frames. The release for them was sublime. Truly, a gift from above.

I used to think mine was a highly rewarding job.

I gave people something.

I gave them hope.

Waste of time? Yeah, mostly.

2. Paralipophobia / par′ă-lip′ō-fō′-bē-ă / fear of neglecting one’s responsibilities

I’m into violence.

Yeah, not machine gunning rap stars or anything, but I love a good fight.

Short Bus Hero

Short Bus Hero