- Home

- Shannon Giglio

Short Bus Hero Page 3

Short Bus Hero Read online

Page 3

Ally slips to the floor and thrashes about, unleashing a furious staccato of fists and heels upon the matted shag carpet. Lois does not enter the family room until the melamine coffee table is flipped on its side with a loud thump and Ally begins screaming.

“…is engaged in talks with the Worldwide Wrestling Coalition, to discuss the possibility of a buyout,” a plastic woman on the cable news finishes. “In other news, yet another strange creature has washed ashore in Mon…” Lois aims a remote control, scavenged from beneath a pile of unraveled yarn (which had once been an afghan knitted by some stranger) on the couch, and silences the woman. She turns her attention to her screaming child. Ally, my Dear One, is twenty-four years old. She has been throwing tantrums for twenty years. Oppositional behavior is common among our kind. Lois is highly experienced in such situations. She pulls the coffee table away from Ally and moves a worn plaid wing-back chair to a safer position, deeper into a pile of abandoned clothing.

Then, she waits.

Her eyes pass over the jam-packed bookcase, absolutely crammed full of broken-spined paperbacks, some dating as far back as her high school days, a bazillion years ago. She gazes at the tower of old vinyl record albums in the corner. Why they keep those, she doesn’t know. That’s Earl’s collection (his only one). They don’t even own a turntable, for gosh sakes. But, she supposes, like the magazines, they all mark some long dead time that they risk forgetting if they throw them out. The end table next to the chair houses her collection of coasters: coasters stolen from corner taverns, bowling alleys, purchased at Disney World and Cost Plus. You can’t close the drawers all the way because the damn things stick out everywhere. She really needs to find someplace else to put them. But where? Every horizontal surface is already piled high with stuff she keeps because she is convinced that she’ll need it the second she throws it out.

Ally wears herself out. Her screams become intermittent. Her drumming slows. Tears dry on her cheeks and neck, and her eyes open by degrees. After two minutes and forty-one seconds, her wailing has been reduced to a dry hitching, and she sits up, a scrap of notebook paper stuck to her ear. She wipes a bubble of clear snot on the back of her pudgy hand.

“Ready?” Lois asks, peering at her over the top of her glasses.

Ally’s father, Earl, enters via the kitchen, squeezing along the goat path through the adjoining dining room. A rectangle of duct tape clings to his sneaker and makes a little “pppt” sound with every step he takes, until it catches a plastic shopping bag, which Earl bends down to remove and tosses onto a pile of old broken dolls. He’s been in the garage, sorting the recycling. That’s probably where the duct tape came from. As a recent retiree, hanging out in the garage and recycling have become Earl’s favorite hobbies. He’s begun to sneak some of Lois’s collected trash to the dump, thinking she doesn’t know. He only takes a few things at a time—a short stack of newspapers, a couple pairs of shoes, a broken lamp from a hiding spot in the rafters above the garage. He wonders how long he can keep it up before she notices. If he hadn’t started that, they would have had to move out of the house a year ago. He lives in fear of the day that she looks at him and says: “You know, I’ve been looking all over for that duck decoy lamp we bought at the flea market. I know I put it up in the attic over the garage.” Oy.

Earl stops short when he sees Ally, red-faced and snot-wiping, on the floor. “What’s wrong with her?” he asks Lois. Lois shrugs her shoulders and turns back toward Ally. Earl wouldn’t understand even if she could tell him why Ally was freaking out. It’s not that he doesn’t care, it’s just that he’s not Mom.

“What happened?” she asks.

“He’s- He’s-” Ally’s mouth locks in a stutter, a white clump of spittle clings to the corner of her lips. The Formans call this “getting stuck.” Ally’s stutter turns into a ratcheting jaw, fluttering eyelids, spinning eyeballs, and a desperate flapping of the hands. Ally gets stuck often. It frustrates the hell out of her. She knows exactly what she wants to say, it just won’t come out. “He’s going to get fired,” she finally forces out in a rapid shout.

“Who?” Lois asks.

“Stryker!” Ally cries, pulling at her hair, crawling over low mounds of junk to the comfort of her mom’s embrace.

Lois is not surprised by her daughter’s reaction. She knows how Ally loves Stryker.

All her life, Ally has gotten extremely attached to various people and objects. They come and go in waves, but Stryker has lasted much longer than anyone or anything else. The My Little Pony, the Blue’s Clues, the Luxor Mummy trading cards, the whole pirate thing. The wrestler has outlasted even the timeless Barbie dolls that Ally collected for years and just recently started playing with again.

Ally’s attachments are classed by some as part of an obsessive-compulsive disorder. Others are of the opinion that such behavior is merely another manifestation of her Down syndrome existence, like the white flecks in the rings of her blue irises, or her flat facial features. No one knows for sure, but strong emotional attachment to various people and objects is not uncommon amongst the Down syndrome set. Ally is just a little more extreme. Lois has learned not to question it. “It is what it is,” she frequently repeats, silently and aloud. Ally’s family deals with it, ignores it, integrates it into their lives.

Lois holds Ally as she weeps. Earl retreats to the kitchen, in search of a Bud Light, leaving his wife to comfort his daughter. He isn’t much good at that kind of thing. Driving to the mall, fixing broken computers, sorting the recycling, that’s what he is good at. He shows affection by doing things for his family, providing for them, taking care of them. He leaves the coddling to Lois.

Ally wipes her nose on Lois’s shoulder, leaving a wet smear like a snail’s trail on her mom’s black Steelers sweatshirt.

Most people are surprised to hear that large numbers of the Down syndrome community are avid wrestling fans. It’s totally true. Go to any match and look at the VIP areas, the accessible seating. Ally and her friends not only attend performances in their home city, but they regularly trek to neighboring states for matches. They spend every cent of their meager wages, earned at menial job placements, on pay-per-view events, t-shirts, action figures and dolls, officially licensed notebooks and bed sheets, DVDs, magazines, anything they can find with their heroes’ images on it. Those Dear Ones visit the official websites, the unofficial websites, post in the wrestling forums, obsessively check match results, blog, tweet...

Wrestling is essential to their lives. Vitamin W.

Ally’s typical day involves bagging groceries at a local supermarket where she is teased by a nasty pimple-faced stock boy, pitied by well-meaning cashiers, and mostly avoided by customers who don’t want to catch her stupid. Her family treats her like a child and her mother tells her what to do every minute she isn’t at work. The only thing out there that gives her release from the tedium, the only thing that lets her pretend she’s one of the unremarkable cheering crowd is…

Wanna guess?

Yes, the wonderful world of wrestling!

Ally comes home from work, always before eight o’clock, and either gets together with her tight group of friends, the Cool People, or she chats with them online. And what do they love to discuss more than the next American Idol and Twilight? You got it, wrestling. They spend hours talking about Nyxxa pounding the snot out of Dandy Dean. They go on and on about who won the most matches ever in the city of Memphis. They know who is the heaviest heavyweight. They speculate on who uses steroids and who lives up to their own standards of eating clean and working out hard. They trade pinups from magazines and decorate their bedrooms.

Ally’s room not only contains photos and posters of her beloved Stryker; she has an actual championship belt, a laminate hanging from an official AWG lanyard, and pictures of herself with almost every top wrestler in the business. Not uncommon among the disabled. Those kids get to meet all the stars, man. It’s just about the only perk they enjoy.

She and her

friends just can’t get enough of the wrestling scene.

So, why are these Dear Ones so consumed with this “sport”? Tough to say. Perhaps it is a fantasy involving physical perfection and strength. And the good guys, those whose hearts are pure and true, always win in the end, no matter what the odds (well, that was true in the olden days, anyway).

You could say pro wrestling gives them hope.

Waste of time? Um, not as much as you might think.

But, what’s Ally going to do without Stryker?

4. Veritaphobia / verˈ-i-ta fōˈ-bē-ə / fear of truth or reality

The serrations of Stryker’s knife blade catch and tear at the gray fibers of his overdone Sydney Sirloin, sawing it into a frayed disaster.

“Sorry I couldn’t meet you any place nicer,” Stryker’s prospective agent, Alan Rush, says, across the narrow table. He sneaks a sidelong glance at the giggling two-year-old who keeps peeking at them over the faux oak partition. Where are that kid’s parents? “I mean, it was kind of short notice, you know, and, well, Ayers Rock Café used to be pretty cool, right?”

Yeah, maybe in the eighties, Stryker thinks. It has since become a family place, about three rungs below the Outback Steakhouse on the cool-restaurant-o-meter. Stryker could have thought of a better place to meet, especially to celebrate his lucrative new WWC contract. But, Rush sounded anxious on the phone, said he had some “bullshit” to talk with him about. Ayers Rock just happened to be the closest place, not counting the Burger Chain.

“Yeah, it’s okay,” Stryker mumbles around a lump of stringy flesh hanging out of his mouth as the eavesdropping two-year-old is snatched from his perch, belting out a piercing wail. He’s sorry to see the little guy go. He reminded him of someone, older now, a teenager, living with his mother and new father, somewhere on the outskirts of Boston. Or, at least, that’s where the kid had been the last he’d heard. Some obscured memory fought to surface in his conscious mind, like a drowning victim.

I can’t see through the murk. I wish I had been following Stryker from his beginning, but, alas, he wasn’t identified as “pertinent” until a few years ago. Dammit.

Stryker flips an internal switch and gets back to business, leaving the memory behind some mental iron curtain. “So, you gonna keep me in suspense all freaking day? Am I getting the six mil or what?”

Rush drains his nearly empty champagne flute, touches his napkin to the corners of his lips, and drops his eyes. He clears his throat several times and loosens his shiny necktie.

An agent in the world of professional wrestling is not the same as an agent in other fields. It is not an unbiased party, working to make the best deal for his client. In the biggest wrestling organizations, an “agent” is merely a mid-level manager, someone who acts as a liaison between the wrestlers and the higher-level executives, someone who works the storylines, keeps track of who’s hot and who’s not. Rush had been a wrestler who worked with Stryker back in the early days of the AWG. He had since defected to the much larger WWC and worked his way up to his current agent position. As an old friend, he was doing what he could to find Stryker a job. He thought he had, but after an early-morning meeting that day, he discovered he was wrong. The higher-ups said Stryker lacked personality, wasn’t hungry enough.

Rush pushes back from the table. “Excuse me, huh, donniker?” He drops his napkin on his seat as Stryker points him toward the platypus-adorned neon restroom sign. “Donniker” is a carny word for bathroom. Rush is an old-school crook.

Despite Rush’s nervous behavior and the trouble with the AWG, Stryker doesn’t get the sense that there is anything at all amiss. But, he is not the most attentive to subtle behaviors, which his ex-wife would be the first to corroborate, given the opportunity. He flags down the waitress and orders a Bud Select to wash down the bottle of champagne he’s already quaffed. Thick as he is, he did catch the quick lascivious wink she dropped his way. Too bad she’s a bit thick in the ankles for his taste. He picks at the remainder of his loaded baked potato and surveys the psychotropic dining room. It’s filled with over-the-top stereotypical-yet-bizarre Aussie décor: stuffed kangaroos dressed in disturbing costumes (one is a 1920s gangster, another wears a latex suit and a ball gag, a third is wrapped like a mummy), a series of surreal paintings featuring koalas wearing molten metal sunglasses, shrunken Aboriginal heads. It’s worse than Planet… oh, you know.

It isn’t until Rush returns with scarlet swooshes floating high on his pale cheeks and beads of sweat dotting his smooth forehead that Stryker begins to think something could be wrong.

“Okay,” the wrestler says, “so, how does this work?” Rush wedges himself into his chair, laying his napkin in his lap. Stryker leans over and peers under the table. “I don’t see no briefcase or anything. Shouldn’t we look at the contract? I would think they’d want that signed ASAP, right? Make everything official and whatever.”

Rush heaves a sigh that rustles the Splenda packets in their ceramic holder at the edge of the table. He stares at the rubble that is Stryker’s plate. He clears his throat again. “Um… Stryker...” Rush chews his lip, fingers his water glass, fidgets in his seat. “Um, see, it’s, uh… It’s not you, well, not exactly…”

Something is rotten.

Duh.

He should have known. It was absolutely ridiculous to think his old buddy could just waltz into his boss’s office and ask him to give his newly out-of-work pal a six million dollar job. Stryker curses himself for being such a complete idiot. A kernel of panic pops open somewhere inside his rib cage as he reviews his actual job skills in his head. His massive hand balls into a fist beside his plate. Rush’s lips move, but nothing comes out.

“What? What are you saying, because I can barely hear you.”

“I, um… Stryker, they’ve decided not to offer you a contract.” Rush squeezes his eyes shut and braces himself against a flying object: fist, bottle, latex-clad kangaroo. He holds his breath and waits almost a full minute. When his old buddy does not strike him, he first opens one eye, then the other, and relaxes his creased forehead. The wrestler stares at him, slack-jawed and wide-eyed.

“What?”

“They’ve decided not…”

“No, no, no, no, no—don’t say it again,” the wrestler spits, as if the mere act of repeating the statement will make it come true. It has to be a joke. Rush is like that, always playing jokes. Like the time they’d hit that buffet at the Indian casino after a match, and Rush pocketed a handful of shrimp and spent the rest of the night stuffing them underneath slot machines. A week later, they went back and the place reeked of rotten shrimp. Funny. “Goddamn. You gotta be yankin’ me.” Stryker runs an enormous hand through his black mop and grins. “Don’t you play me like that, you old sumbitch,” he says, pointing an index finger into Rush’s face.

“I’m sorry,” Rush whispers. He does not give the appearance of someone who is yanking anything. On the contrary, he looks disappointed and regretful, forcing the wrestler to once again think of himself as an idiot.

The news sinks in. The smile fades. An invisible icy fist twists Stryker’s innards. He curses himself again for being a fool. “Son. Of. A. Bitch,” Stryker whispers. What does this mean? What does he do now? He has no idea. He has no education, no marketable skills, no savings, no rich relatives. What he does have is an epic mortgage, unbelievable car payments, and an ocean of debt.

A cloud of confusion settles around his head like the rings of Saturn. He can’t see clearly. He can’t hear properly. Nothing exists beyond the asteroid belt of problems encircling his head and the doom ringing in his ears. He has to get out of there, out of the artificial Outback. He stands up, inadvertently tipping the table toward Rush, spilling his beer. He rips the napkin from his shirt collar, throws it on the table, and stumbles out of the restaurant, ignoring the gauntlet of fans calling his name all the way to the front door.

Stryker has been a good solid draw for almost six years. The AWG sold millions of t-shirts and po

sters adorned with his image. He was an A-Team wrestler, always figuring into the biggest storylines, always giving every performance everything he had. He limited his use of steroids, worked hard at keeping his body fit, and was always gracious to his many, many fans. He could not believe the WWC didn’t want him. They were taking Gemini, that freaking backstabbing old hack. No wonder he’d been so distant lately. He was getting the big deal that should have been Stryker’s.

Son of a bitch.

Stryker refuses to believe this is happening.

He somehow finds his black Navigator, fumbles with the door, and slams himself inside. The numbness he felt in the restaurant is burned away by a searing terror. Rage pilots his fist into the XM receiver lodged in the dash, cutting the knuckles of his right hand, eliciting a flood of explicit language from his mouth. His cell phone sounds a ringtone he assigned to Alan Rush. Pink Floyd’s “Money.” He drops the cell onto the floorboard and stomps on it with the heel of his motorcycle boot.

A tap on his window interrupts his brutish outburst.

Rush stands, phone to his ear, peering in at Stryker through the tinted glass.

Stryker slams the key into the ignition and peels out of the parking lot, leaving his “agent” standing there, still holding his phone.

***

Middle of the night.

Stryker staggers through a nine-paneled dark cherry door and falls to his knees in front of an ebony toilet. His mouth yawns and sticks, a deep belch forces its way up from the depths of his intestines. The sonic quake is followed by a fragrant torrent of sepia-toned fluid littered with mahogany clots and capillaries. Most of the spew cascades into the toilet bowl. Much, however, colors the plush white rug beneath Stryker’s knees, making it look like someone spilled a cup of strong tea.

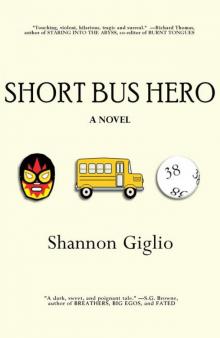

Short Bus Hero

Short Bus Hero